The following was a result of a handout I put together for a workshop. More detailed information can be found about these topics in separate blog posts on this site.

Establish a solid practice schedule:

- Actually block off time in your schedule designated specifically for practicing. Avoid using it for lunch, socializing, homework, errands, sleeping, and so forth. As a musician, practicing is part of your job, so treat it with professionalism.

- Write your designated practice time in your schedule. Enter it into your online planner. Make sure it ends up wherever you will see it until it becomes habit.

- Arrange your practice time for when you practice best. Some people love getting work done first thing in the morning before anyone else is around to be a distraction. Others work best late at night. Maybe right before or after lunch is when you’re most alert. Figure out when your most effective practice time is and make sure you schedule around that. A reasonable amount of focused practice is better than lots of unfocused practice.

- Your practice time doesn’t have to be one large block. Maybe you have 30 free minutes between classes early in the morning. That’s perfect for your warm-up! You can then schedule another practice session for technical work and repertoire, or you can split that work into two sessions.

When approaching a new piece:

- Listen to a quality recording of the piece. Yes, this counts as practicing!

- Do a quick run-through of the piece to get a feel for it and where the difficult parts are.

- Actually write the tempos of each problem area in your music (in pencil) so you remember where you are the next time you practice. You will probably have different tempos for each difficult section of the work, but that’s ok. You’ll eventually work them all up to the same tempo. Don’t forget to update the tempo in your music after you’ve made progress.

- In particularly difficult sections, it may be necessary to break your practice down into just 2 or 3 notes. This may seem too simple, but it’s a much more effective use of your practice time than simply running through the music and making little, if any, progress.

- Save run-throughs. Start doing more of these as you approach a performance to get a feel for the work in its entirety and to start building endurance. It’s also helpful to do occasionally to assess how well your practice is going, but it’s simply not enough to be your sole practice strategy.

Handling especially difficult sections:

- First, make sure you’re practicing slowly and with a metronome. Play it as slowly as needed so that you’re able to play the entire passage correctly. This may be half-speed or even slower. That’s ok; you’ll speed it up later.

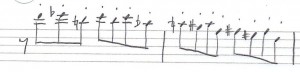

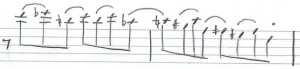

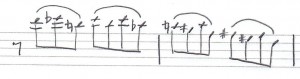

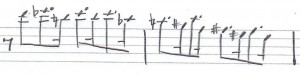

- Second, try playing the passage with different articulations. Try slurring the difficult passage, articulating it, slurring small and large groupings, and combining articulations and slurs.

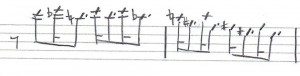

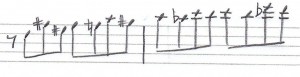

- Third, alter the rhythm of the passage. If the passage is made up of eighth notes, play a dotted eighth/sixteenth note pattern. Then reverse it and play a sixteenth note/dotted eighth note pattern.

- Finally, try playing the passage backwards. This gives your brain and fingers a serious workout. Practice this section backwards until you can play it smoothly and comfortably.

- Once you’ve practiced this difficult section with all of these changes, play it as written. Even after a short amount of practice, you should see considerable improvement.

How do you know when you’re improving?

- Checking metronome markings. This is a pretty simple way to measure progress, especially in technical passages. Being able to play something a few clicks faster than you could at the beginning of your practice session is a pretty good indication of progress.

- Being able to play longer passages in a work. Maybe you could play only small portions of a work previously. Maybe you could only make it through one movement before you felt fatigued or lost focus. Suddenly, you can make it through the entire piece successfully. This is a positive sign, especially if you are getting close to a recital date.

- Noticing an improvement in tone quality. This issue becomes more subjective. Recording yourself, an eye-opening experience, is a great way to hear what your audience is hearing. The sound from the performer’s side of the instrument can be vastly different from what the sound is by the time it reaches the audience. Maybe you’ve been working on tone and you *think* it’s clearer, more resonant, more focused, and so on. Double-check it with your recording device.